Imagination

We had a wonderful conversation with a three year old student about imagination. It went something like this: "We love your new tie-dye shirt. Can you tell us about it?" The boy responded thus, "I made it with my mom." With a grin on his face, he enthusiastically continued, "We colored the world." His mother, looking as proud as a peacock, rejoined, "How about that imagination?"

Now, this exchange instantly jumpstarted a series of questions: What is imagination? How is imagination to be understood? Is it possible to teach imagination? Do our judgements inform imagination? Further still, and to encapsulate our fundamental question: what role does imagination play in education?

Imagination, to be sure, is extremely difficult to define. There's no ready-made taxonomy for thinking through imagination. Interpretations vary widely. Traditional accounts, philosophical as well as cultural, typically put forth the thought that imagination is, roughly speaking, an ability to form a mental representation of something imagined.

An example of this characterization is as follows. You instruct a three year old to close their eyes and imagine life on Mars. "Use your imagination", we encourage, as we hand them a blank piece of paper and a packet of colored pencils. As a part of the exercise, perhaps we lay out the basic criteria of the terrain, i.e. "Mars is a planet that is hot, red and far away. There may be life there," we mention. "But, we can't be sure."

A few minutes later, we return to the table to see a small red circle enflamed with what appear to be ants, or aliens. We can't quite make it out, but we surmise that the purple colored flecks are invading the surface of the planet with vigilance. "What intelligence", we think to ourselves, as we praise his imagination, and his creative application.

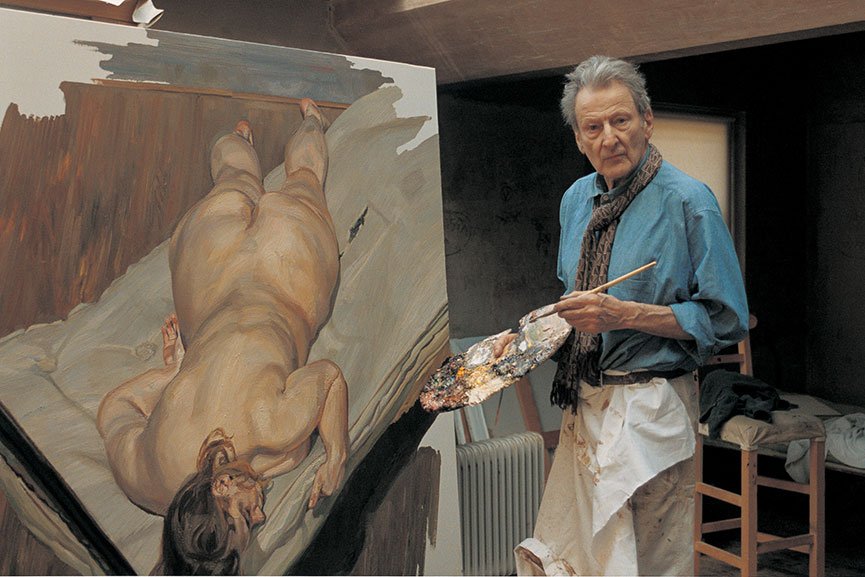

The great British painter Lucian Freud, however, develops another approach to imagination. In almost direct riposte, he claims: "a great deal of what is normally thought of as intelligence, is actually imagination - that is, an ability to see things as they truly are."

With this assessment, Freud arrives at a new definition of imagination. It's important to note that for Freud, imagination is not belief. Nor is it memory or perception. Least of all, is it fantasy. As a matter of fact, imagination has nothing to do with fantasy or constructing other worlds. Yet, we have a tendency to confuse and jumble the two together.

Imagination, thinks Freud, relates directly to experience. When prompted to discuss colors, for instance, and why he doesn't like taking drugs, he observes: "People say such things as, "Oh, they make me see such marvelous colors" - which to my mind is a horrible idea. I don't want to see marvelous colors. I want to see the same colors, and that is hard enough. Then they say that they are taken out of this world, but I don't want to be out of this world. I want to be absolutely in it, all of the time."

Real imagination, as he describes it, is an 'ability to see things as they truly are'. Imagination, then, is running wild with your own thoughts. It's not about creating things that don't exist, but exploring potentialities that already exist, and pushing them to new limits.

In many respects, the question "what if…", is the beginning of imagination. It's not about coloring in the lines, or following instructions. Rather, it's about creating your own lines, taking charge of creating your own world, with your own coordinates. If education has a role to play in imagination, it's in setting it free.