One Thousand Tears or More

There’s an entire history of books consumed by flames. Our memories lay purchase to their cultures, and we become witness to those who endured the endless fires. For some, the flames can still be seen, even if they are but mere flickers, unsteady bursts of light suspended by time, trapped in the distance.

Less is known about how many books actually met a watery fate, as opposed to an incendiary celebration. Water is somehow less symbolic than fire. Perhaps it’s more tepid or languid, or even calming. It has a wistful, unassuming smile, one that is always ready to seduce, to lure us into thinking its powers are only those of enchantment, when it’s really concerned with an immemorial embrace.

We wince at the horror, as we read about the Library of Alexandria. Its constant destruction pains us still, especially in the context of what it means today. We cringe to learn that Emperor Qin ordered all philosophy books burned, and the authors who wrote them mercilessly buried alive. Or, when Sartre shares the maladies of the imprisoned Jean Genet, our soul itself is seared by the injustice and fervor of the flames.

There’s something magical and powerful about books. What they set free, what they contain.

What the prison guard took from Genet, as he burned what would later become his autobiography, Our Lady of the Flowers, was not just his hope for release, or the promise of recompense. No. He attempted to take his humanity. As Heinrich Heine famously said, “Where books are burned, in the end people will be burned.” Whether it happens all at once, or over the slow, methodical course of many years, it eventually happens. It takes time, patience and cleverness, to amass the tinders needed to sustain an everlasting fire. Yet, there’s an inevitability to it.

Lest we forget, the community which built the Library of Alexandria into a center for worldly scholarship, that bolstered its very occasion, is the same that watched it burn. While Emperor Qin administered the orders, they were almost certainly carried out by someone like us. Wasn’t that Arendt’s exact point about Eichmann? We are all complicit in the story of our lives.

We can almost, each in our own way, see the papyrus as it incinerates, forever serving as a beacon for an eternal, creative struggle, and a calling card for more sinister sides. There will always be those who try to oppress that which needs to be heard. We envision an amber colored chorus of ruination, as scrolls hurriedly ascend, desperately trying to escape their impending annihilation, recklessly and courageously grasping for the life that birthed them.

If we listen, with just the right amount of intensity, with our ears pressed to the wind, we can hear their faint, smothered screams. Those of the books, and those of the steady hands who wrote them into existence. After all, it takes great strength to commit an idea to the world, and even greater strength to stand by the convictions of the ink-stained words, (especially as time passes, and they become harder to decipher, and easier to smear). There’s a reason that the Origin of Species remained in Darwin’s desk for all those years. It’s easy to turn a sorcerer into a hero as they’re doused and mounted to a stake. It’s harder, to be sure, to take solidarity in the struggle, when it’s your own flesh that starts to burn.

Of course, there are stories of books that famously escaped such undying infernos. One only need remember Max Brod and his abiding betrayal. Oh, the treachery! Here’s Kafka: “My last request: Everything I leave behind…in the way of diaries, manuscripts, letters (my own and others’), sketches and so on, to be burned unread.” As his words take hold and start to register, we are reminded that most of us would be honored, if we had anything worthy of such a breach of trust. I suppose there’s always hope.

With hope comes a sense of responsibility.

After a recent weekend excursion, more of an outstanding family-obligation, we returned home to find our unfinished lower level completely flooded. Standing atop the staircase, peering down into the watery basement below, we unexpectedly observed three inches of water, standing just so, glimmering, shyly, for our attention.

In a way, it was as if the pool of water, as it slowly mounted the abyss, had solicited our tears - much to the chagrin of our affection for the adventures of Alice in Wonderland. We wondered how many tears had participated, knowingly or not, in libricide.

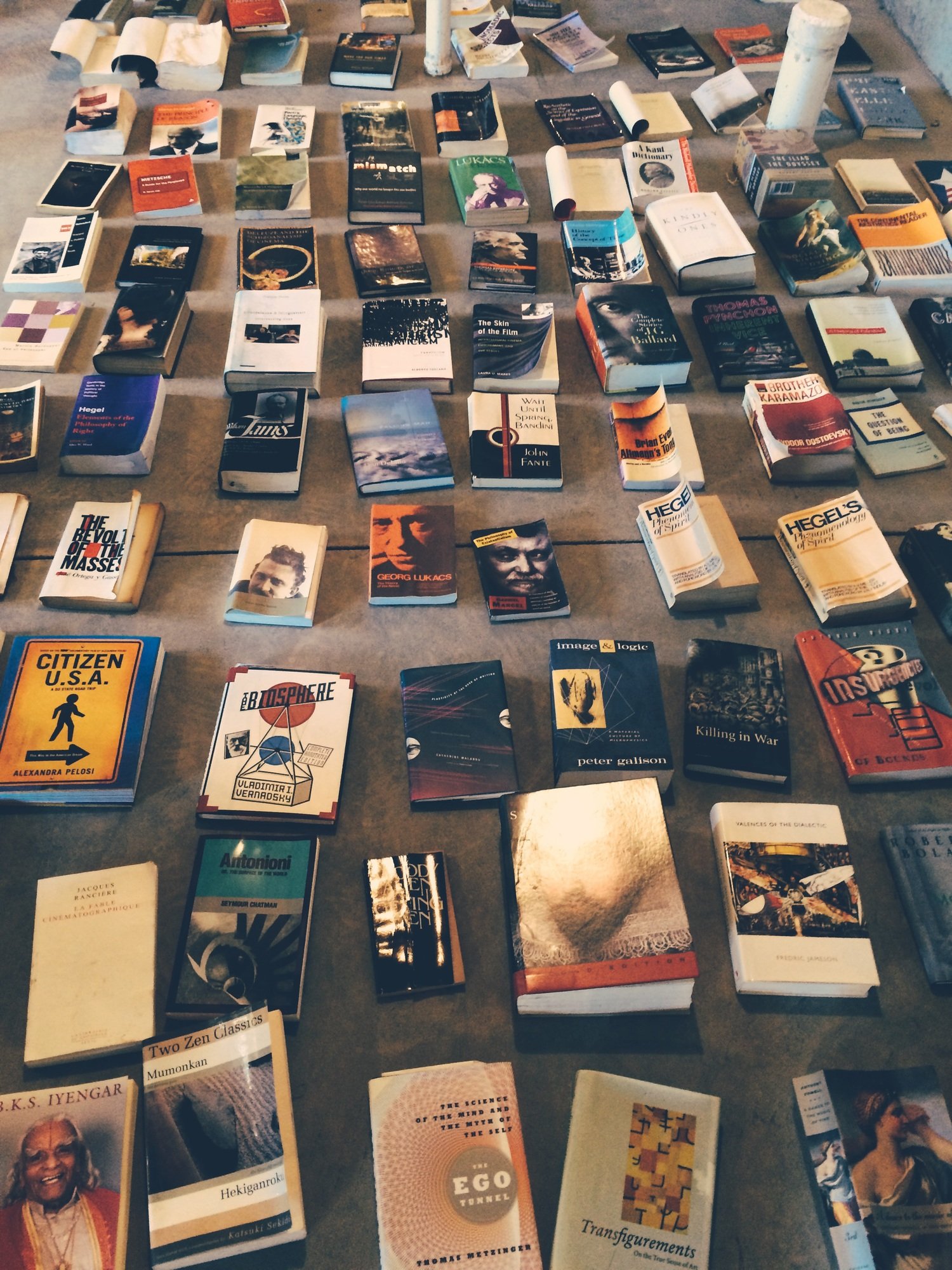

Quickly, as we took inventory of the contents, we were brought down to size, discovering our collection of books, completely immersed in the seemingly innocuous, rising water. The cardboard boxes, neatly, alphabetically stacked against the concrete wall, twenty x three, or maybe more, steadily started to succumb to the weight of the water. Hurriedly, we waded through the increasingly untenable basement, rushing to save the unaffected books, those carefully positioned atop the sturdy boxes below.

After scaling the stairs with the rescues in hand, we anxiously made our way to the bottom layer, to those boxes most heavily affected, having absorbed the burden of the water. As we opened the shrinking boxes, pealing off the top few layers of salvageable books, we apprehensively made our way to the list of authors, whose titles were now soiled beyond respite.

We recited aloud the names of those who never deserved their books to meet such lack of providence, perhaps despite their intentions to the contrary.

“Nabakov, Miller, Perec…”

“All of Nabakov? Even Lolita?”

“Yes, even Lolita.”

Muttering to the cadence of the work:

“The…light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.”

I distinctly remember an adjunct philosophy professor at Lehigh University, where I completed my undergraduate, who had returned home from a day of lectures to find his second-floor apartment ablaze. His only real concern, as he later relayed, was the state of his books. Had they all been burned? Could any of them be saved? Understandably, he was beside himself, watching his life’s work catch fire.

In an act of resistance, he showed up the very next day with a seared copy of Illuminations in his hands. He hadn’t slept, let alone showered or changed his clothes. Soot was everywhere. In his hair, on his briefcase. As he carefully turned the page, trying to stay focused on the task at hand, which if I remember correctly was teaching the "Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction", ash literally drifted off into the air.

What does it mean to lose a book? Or a library? It’s not just the physical nature of the book, the parchment and the ink. It’s not just the efforts of the author, and the import of their worlds. It’s the margins too. The underlines and circles, the points of emphasis. The notes and the conversations with the author. Even the disagreements. Those are important too.

We covet libraries, just as well as books, not just for their contents, but also for their promises. Books are memories - of places purchased, of journeys discovered, of romances consummated. They’re grand adventures that we can constantly relive. They also help us to make sense of things. Books order memories - of lived dreams, of forgotten ideas, of times yet to come.

They were in my care, these books. They were entrusted to me, as much as to history. It was my responsibility. My fidelity. There’s a sense in which I feel like I betrayed them. That I disturbed a certain order of the world-memory.

At the Library of Alexandria, it is reported that there were “books of the ships” which were sorted, cataloged, and then shelved. These books had arrived through the ports, having made the voyage across the Mediterranean sea, presumably from Greece. They had found themselves inscribed amongst a new collective. When the Library of Alexandria was destroyed, those books weren’t separated, or set out to sea. They burned with the rest of them.

Of course, we would much prefer to share our notes on how to organize a collection of books, or engage with Walter Benjamin’s excellent essay on unpacking a library. Instead, we find ourselves, reluctantly, preparing to write a eulogy to our library. Or, rather, a confession to our heroes and the books they shared with the world, despite the fires they may have incited.

It’s the one letter we never expected to have to write.